The best role models are the improbable ones ― the ones who don’t strut or gloat or feel entitled when they become rich or famous. They embrace where they came from, holding that close while paying it forward.

Bill Knapp, who died Nov. 15 at 99, was one such role model. And Des Moines is poorer without him.

You might not have known from his small stature or gregarious laughter ― sometimes at his own expense ― what a towering force Bill was. You couldn’t have foreseen that the Wayne County kid working the family farm during the Depression would ultimately be credited for Des Moines’ urban renaissance. As founder of Iowa Realty, which would become the state’s biggest real estate development company, Knapp shepherded in apartment buildings, restaurants, hotels and much more.

While serving on a Des Moines revitalization committee in the 1980s, he visited the quirky Fog City diner in San Francisco, later featured in the Mike Myers movie “So I Married an Axe Murderer.” Knapp returned to Des Moines determined to build a venue like that for our college community. So the Drake Diner came into being in 1987. The popular Des Moines eatery has outlasted Fog City, which ended its run this year.

Des Moines’ skyline, especially magical lit up after dark, is also attributed to Knapp.

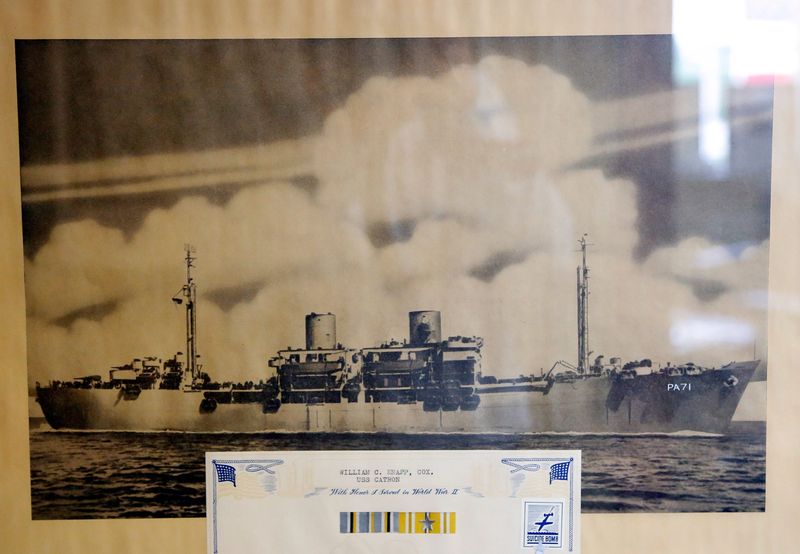

From the light Knapp radiated, you may not have guessed what darkness he witnessed. He enlisted in the Navy at 17, serving during the World War II Battle of Okinawa, which claimed more than 300,000 U.S. troops from April to June 1945. Bill personally carried some of those bodies onto the landing craft he navigated, to deliver them home.

But if war taught him the fragility of life, it also made him appreciate his life and learn, in his words, to live each day as if it were his last. That grew to mean opposing unnecessary wars, like Vietnam. Bill’s good friend Bonnie Campbell recalled that, when U.S. Sen. George McGovern got the Democratic presidential nomination in 1972, his evolving opposition to the Vietnam War didn’t sit well with many. But, as Knapp told Campbell, “The people who support wars have never been in war. You can’t have the experiences I had and support war.”

The stories of Knapp’s generosity, both institutionally and personally, abound. They include his $3 million donation to Drake University for the 6,424-seat Knapp Center arena to his support for the Evelyn Davis Tiny Tots Childcare Center to his multiple contributions to the Iowa State Fair. His donations could be spontaneous, like one inspired when the Knapps attended the Aspen wedding of their good friends Roger Brooks and Sunnie Richer 35 years ago. Bill told the minister the carpeting in the chapel was worn. Then he wrote out a $30,000 check to replace it.

He also donated the land for the Iowa Veterans Cemetery, where he is now buried.

But his investments in people he cared about were no less significant. His nephew Bill Knapp II ― who, in his own words, flunked out of college ― worked for his uncle for a time and went to law school at his urging. “He gave me opportunities long before I was confident or thought I could do the work,” he told the crowd at his uncle’s Plymouth Church memorial. He witnessed up close the egalitarian way his uncle treated employees, describing him as a “pioneer” in profit-sharing and stock option plans. “He always gave credit to his employees, saying. ‘They don’t work for me. They work with me,’” he said.

Not that his uncle was always easygoing, Knapp II added. “He was tough, direct and very much to the point. But he was very forgiving and understanding, and he never, ever held a grudge.”

Bill Knapp also offered advice to Greg Abel, who reached out to him on moving to Des Moines as president of MidAmerican Energy. Knapp told him a lot needed fixing at the utility company, and encouraged him to be a good corporate citizen as it got stronger.

Abel is now replacing Warren Buffett as CEO of Berkshire Hathaway.

Knapp encouraged Campbell to go to law school while she was chairing the Iowa Democratic Party. She did, and he later helped her get elected Iowa’s first female attorney general. Campbell went on, in 1990, to write one of the nation’s first anti-stalking laws. Later, then-President Bill Clinton appointed her as the first head of the U.S. Justice Department’s Office on Violence Against Women.

Some of the most touching testimonials to Bill’s generosity came from his stepdaughters, Anna and Sarah. Their mother, Susan, married Bill after her first husband died when the kids were little. Bill was 60 and his own children were grown. But instead of fleeing, as one sister described it, “He stayed, and showed up every day for the next 30 years,” never raising his voice or judging or criticizing them.

In what Anna called “one of the greatest gifts,” he supported her in getting a graduate degree in counseling, and she now has her own practice.

Sarah called her stepdad a feminist and champion of human rights who “radiated love for our Mom every single day.”

I witnessed that love. It was playful and protective, collaborative but respectful of each other’s independence. My late husband, Rob, and I became friends with Bill and Susan through mutual friends early in our Iowa days, and separately lunched with him at his preferred spot, Nick’s Bar & Grill. I don’t know what they talked about, but business seldom figures into my conversations. We talked politics, social issues and elections.

Susan and I have had our own share of outings and quality time with her lively daughters. A high point of the Christmas season for Rob and me was the Knapps’ annual pre-Christmas party. Attended by CEOs and politicians of both parties, in addition to writers, academics, artists and nonprofit leaders, it’s a safe bet their home was the hatching ground for multiple business and political deals.

Though the Knapps were known for their generosity to Democratic candidates and causes, their parties were like giant DEI fests open to all sides. Since Bill’s passing, tributes and acknowledgements have come from key Republican players including Gov. Kim Reynolds and former Gov. Terry Branstad.

Campbell credits Knapp for helping build political “comity in the business community.” Something that’s harder to imagine or achieve these days.

The term “self-made man” has become almost another anachronism as too many Americans don’t see a way ahead. But instead of restructuring monopolies to open more room at the top, our leaders stoke divisions by getting us to blame each other.

Bill Knapp pushed boundaries for himself, his business ventures and the community. He didn’t see those as mutually exclusive. As he told his nephew, “The government should work hard to make the common people succeed, because if they succeeded, the wealthy would succeed.”

His passing leaves many wondering who might fill his shoes. But skills vary, and change agents come in many forms. Just look at Zohran Mamdani’s historic win in New York’s mayoral election ― achieved from the grassroots by through pounding pavements, connecting with people and convincing them how life could be better.

One of Bill Knapp’s greatest contributions was helping people believe in themselves and their own power by taking risks they might not have. Maybe if there’s one thing we can all take away from his legacy, it’s to dream bigger, challenge ourselves harder, and strive to make life better for more people.

Rekha Basu is a longtime syndicated columnist, editorial writer, reporter and author of the book, “Finding Your Voice.” She retired in 2022 as a Des Moines Register columnist. Her column, “Rekha Shouts and Whispers,” is available at basurekha.substack.com, where this essay first appeared.

This article originally appeared on Des Moines Register: Bill Knapp exemplified what a role model should be | Opinion

Reporting by Rekha Basu, Guest columnist / Des Moines Register

USA TODAY Network via Reuters Connect