By Jim Bloch

Novembers are getting warmer.

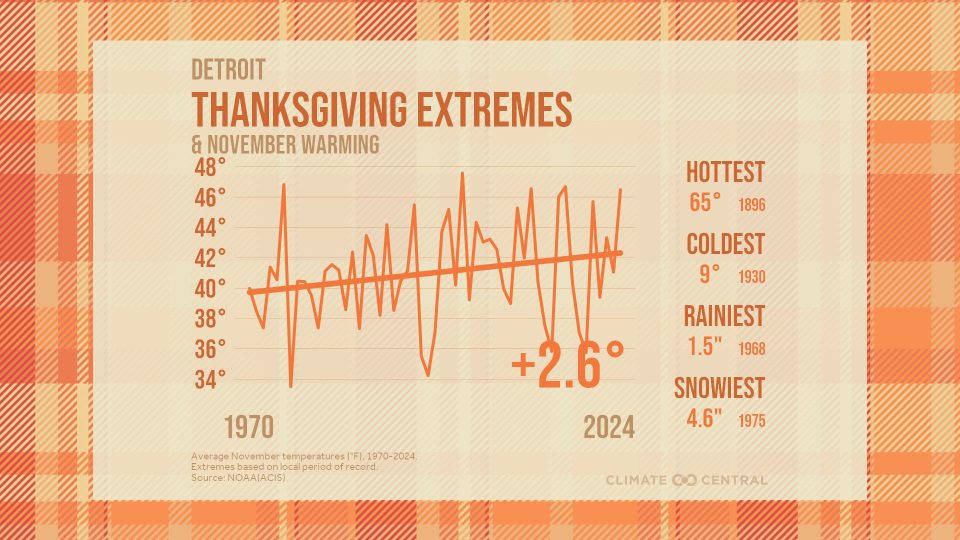

That’s the conclusion of Climate Central, the nonprofit organization that studies climate change and its impacts on the modern world, in an analysis released Nov. 24.

In Detroit, Thanksgiving temperatures have risen 2.6 degrees Fahrenheit since 1970.

“The month of November has been steadily warming up across the U.S.,” said Shel Winkley, a meteorologist with Climate Central. “Our cozy holiday meals are warming right along with them. Ninety-two percent of locations (247) analyzed nationwide have seen temperatures rise since just 1970. We’re talking about an average of 2.4 degrees warmer than it used to be. In nearly a third of those places, Novembers have warmed by more than three degrees. Some of the biggest jumps that are being experienced are cities like El Paso, Phoenix and Las Vegas.”

Global warming began in earnest a century and a half ago, when the people began burning fossil fuels to power the burgeoning industrial revolution, creating the gases, such as carbon dioxide, that trap the sun’s warmth in Earth’s atmosphere.

November in El Paso was 6.4 degrees warmer in 2024 than 1970; in Phoenix and Tucson, it was six degrees warmer; Las Vegas, 5.9 degrees; and North Platte, Neb., 5.7 degrees.

Climate change and food prices

“Here’s how this impacts our holiday tables,” said Winkley. “A warming climate affects many of the foods we look forward to at the holidays. Take cranberries. They’re extremely sensitive to heat. Warming springs can cause the plants to bud earlier, which leaves them more vulnerable to the whiplash of late season frost.”

Wisconsin grows more than half of the cranberries produced in the U.S. Its springs have warmed by 1.5 degree since 1970.

“Hotter summers in the northeast increase the likelihood of what growers call cranberry scald, where the fruit literally overheats,” said Winkley. “As temperatures keep climbing, cranberry growing regions may see a drop in yields, which for you can mean higher prices at the store.”

Scald physically breaks down the berries, leaving them open to fungal invasion, and can result in crop losses of ten percent in less than two days. In New Jersey, the second

leading cranberry grower in the nation, summers temperatures have risen by 3.4 degrees since 1970.

In a feedback loop, agriculture accounts for about 30 percent of the greenhouse gases generated globally, largely via meat production, warming the planet. A warmer planet can impact food production and distribution through heat waves, droughts, more intense storms and other forms of extreme weather, leading to overall higher prices and price spikes.

“A recent study suggests that project warming would drive food price inflation in North America up by 1.4-1.8 percentage points per year on average,” Climate Central said in its Nov. 19 news release on the relationship of climate and the food supply.

In 2022, the drought in California and Arizona triggered an 80 percent jump in vegetable prices that November.

You might like a cup of joe after your big holiday meal. A drought in Brazil in 2023-2024 led to a 55 percent jump in coffee prices; Trump’s tariffs have meant continued price jumps.

Maybe you like chocolate drizzled atop your pumpkin pie. A heat wave in Ghana and the Ivory Coast in February 2024 drove up the price of cocoa 280 percent. The two countries produce about 60 percent of the world’s cocoa. And chocolate prices are still sky high.

Time magazine noted that sweet potato prices may be up 37 percent this year following the devastation caused by Hurricane Helene in North Carolina, the country’s top state for growing sweet potatoes.

Bird flu has impacted 180 million turkeys in the U.S. since 2022, driving up wholesale prices this year by 75 percent, according to the New York Times. Climate change has altered the migratory routes of birds, and the timing of migrations, bringing previous unique populations of birds into contact with each other, increasing the spread – and alteration — of the virus. Turkeys are sensitive to heat and warmer turkey farms could lead to weaker immune systems.

“The warmer than normal weather we’re feeling in November isn’t just about deciding whether you’re wearing a sweater to grandma’s house this year,” said Winkley. “It (impacts) the foods we enjoy and the traditions we love and rely on at this time of year.”

Jim Bloch is a freelance writer based in St. Clair, Michigan. Contact him at bloch.jim@gmail.com.